The Time Vietnam Lost My Dad: From Rural Vietnam to America

23 years. It took 23 years for me to finally hear my dad’s story. On April 30th, my dad asked me if I knew what today was. It was the Fall of Saigon. It’s funny how I was on the leadership board in a Vietnamese cultural club to rediscover my roots yet I still had not fully known my dad’s refugee experience.

He was never one to talk about himself or his past life, except with a few lectures here and there about his struggles. It seemed like he was almost hiding it from me when I inquired about it.

“You won’t understand,” he would say, silencing the conversation. I didn’t know if it was because of the trauma he had gone through or the language barrier between us.

After I moved away to college, I joined a Vietnamese club that I connected with and saw myself growing in as a Vietnamese American. There, I found a stronger sense of pride beyond my own ethnic identity — for the greater Asian Pacific American community.

And I got radicalized. I learned the importance of using my voice to advocate and fight against the unjust systems of power that have silenced our voices, to define our own identities and tell our own narratives, to organize communities and movements that empathizes and resists.

On April 30, 2020, Ngày Mất Nước, or Day We Lost the Country, my dad recounted the time the country lost him. Laced with humor and a playful twist, let me tell you his story.

Retold in my dad’s voice and in my perspective:

**some details may be inaccurate or lost in translation

I lived in the countryside. I was a just country boy, living thirty minutes away from the city of Da Nang. It was a hard life. I farmed all day, every day. I took care of my younger siblings. I collected cow poop to fertilize the crops. Every time the buffalo tail shoots up, I quickly ran over to catch the poop with a bucket and throw it into the fields! I rode the buffalo every day. Sometimes I fell asleep while riding the buffalo and when I woke up, I didn’t know where I had ended up.

There was never enough to eat. The communists calculated and rationed out the food we would get, which depended on the amount of food we grew compared to other families in the area. They took most of the food. I was always hungry. I hid until my grandpa finished eating in order to creep up and eat his leftovers. We never ate at the same table, and he always ate first. When he walked away from the table, I secretly crawled around him to get the food. My grandma loved me a lot, though, and she tried to give me more food.

My dad worked as a bicyclist. Like Uber but on a bike. He was a small man but he was really strong. He would ride from the mountain to pick people up and take them to the city. Ahh man. But when there was a big person, he would struggle a lot, even cry too. One day, the police took him south to work.

My mom was someone with a high status. She was #1 in the area. She was very beautiful but that changed when the entire family split and relocated to the countryside after the fall of Saigon. She had to work very hard too. I even felt bad for her. Most of the people from her family followed the communists. She worked in the fields for a long time, darkening her skin.

She took the train to the city to buy food and resell in the countryside. There was a high tax placed on items coming out of the train station so my siblings and I would check the train arrival time and wait out on the field. At the right moment, my mom would hold onto the train handle and kick the food out of the train door. There would be so much food rolling down the hill because a lot of people were doing this, not just us. Sometimes a watermelon would break in half too. We kept track of our stuff with a color indicator. My mom was in her forties when she did this. She would only carry bigger things, like a jug of wine, out of the train station since there was less tax on fewer items.

My sister secretly sold clothes and fabric from Da Nang to Hanoi. She sold them in trains and hid between the seats. Sometimes she got chased by police inside the train. One time, she climbed on top of the running train to run away from the police. She crawled on top of the train while it was moving. It was bad.

Sixth grade was hard. I got teased and bullied a lot by other kids because my dad worked in Saigon. The teacher was worse and made me hold the Vietnam flag every morning. I hated it. He called me names and insulted me and my dad. I didn’t like the way he treated me. My grandma paddled one of those basket boats to come talk to the teacher about transferring schools. She was old already. The entire time, my teacher called me names. I had enough and just quit school altogether that day.

On some nights, my dad secretly took the train to come back home. No one knew about it. One time, he came home to see his mom, my grandma, because she was getting old. After he left, she passed away in the morning. We did not know he visited because he had to leave quickly to catch the next train to Saigon. If he didn’t, the communists would find him here and punish him.

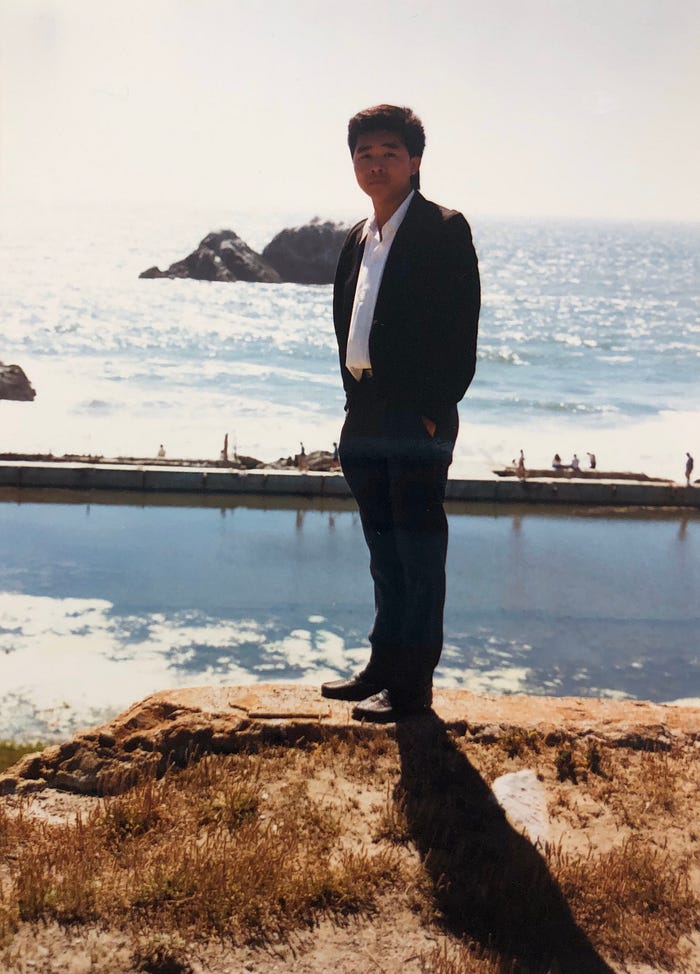

At 16, I asked my parents if I can move to the city. They didn’t want me to go but we let luck decide. They took sticks out. If I pulled out the longer stick, then I can leave. That’s what I did, and so I left. I had never been to the city before so everything amazed me. I looked up and around with my mouth wide open at all the tall buildings!

One day I was just squatting when my uncle saw me and told me to follow him. I did not know where we were going at first. I thought I was going on a trip and wanted to have fun so I just followed him. This uncle was a high soldier in the army against the communists. The communists hated him and were looking for him. He had attempted to escape many times but failed and had been in and out of prison. He was in prison for 5 years before they let him out. My mom helped him hide in our house. I would bring him food sometimes. So that’s how I knew him, and that’s why he recruited me to follow him. Because he remembered me.

My older brothers and dad tried to escape a few times too. They always lost gold or money after getting caught. My dad got thrown into prison for 3 years. But I escaped after only one try, for free, and without knowing the real danger that lied ahead.

There were lots of people. Whole families. That uncle brought his entire family. We would either survive or die. The night before, we slept in the mud because the communists would see our light skin. My uncle told everyone to wake me up or else he would not drive the boat. He was the sailor. But the guy sleeping next to me didn’t wake me up. My uncle counted the number of people and realized I wasn’t there. We were all told to be very quiet or else the communists would hear us.

When I boarded the boat, I was expecting to sit on a chair comfortably. But no! I looked down the hole to the basement of the boat and there were so many people crowded and squished together. It was bad. The boat would go up very high and down very deep. People would throw up in different colors and on top of people’s heads. I was young and from the countryside so I could still endure it. My uncle’s wife had brought some small foods. I ate that but not too much or I would not feel good.

When we saw other boats, we cheered for each other. We would be so happy to see other people. It was a live or die moment. My uncle brought his entire family. It was all based on luck. Five days. It took five days to get to Pulau Bidong, a refugee camp in Malaysia. At 16, I became the only one in my family to escape Vietnam by boat.

I didn’t have my parents with me so I stayed in the barracks/camp for minors under 18, the place for kids with no parents. There were even kids younger than me, as young as 5 years old! And I had to take care of them too. My uncle and his family lived in a nearby camp. I saw him sometimes when we ate together. I met Chú Dung at the camps. We are the same age on paper but I am actually two years younger than him. He is my friend at work now. I wasn’t scared when I was there because there were lots of people around me.

Beginning 1982, I stayed in the camp for about a year. My family thought I was dead for an entire year. It was difficult to live there. I walked a very long time to carry a big jug of water back to the camp. We used that water for everything, from cleaning, drinking, bathing. I had to carry the water for my uncle’s wife too. And I helped her take care of her little daughter.

Later, my uncle and his family immigrated to America first because he was a soldier. Everyone wanted to go to America. They would wait longer, even up to a year, if they didn’t get selected to immigrate to America. People can live in any other country but people liked America. It was the best.

I had an uncle, a distant relative, who immigrated to America before the fall of Saigon. He sponsored me to go to Atlanta, Georgia and stay with him. When I arrived in 1984, I received a jacket from an immigration organization. He was very rich. He owned apartments and stores. I thought he would come in a car but he came in a truck. His wife and daughter came along so there was no room for me to sit inside. I sat in the back trunk. And it was around midnight in Georgia so it was very cold. I only had a jacket. I thought, “This is okay.” I hoped to get rice to eat when I got to his home because I was so hungry. He just gave me cereal and milk. I threw up that night. I thought, “How can he treat me like this?”

(My grandpa said my dad arrived in the US through a refugee program because he did not have family members to sponsor him. I’ll have to ask my dad again to be sure.)

I didn’t like living there. It was hard too. I took care of their daughter and went to school. I was there for a month. My uncle gave me the number of the uncle who helped me escape Vietnam. That uncle was in San Jose, California and very happy there. They sang and danced to cải lương. I told my uncle in Georgia that I wanted to go to California and asked if he can give me some money for a plane ticket. He didn’t want to give it to me.

I had only $60 from the immigration organization and bought a Greyhound bus ticket from Georgia to California. I got lost often and had to take many transfers. I had a Vietnamese-English translation book. I had to ask people for directions while learning from the book. It took 3 days to get to San Jose. I stayed with my uncle and his family. My uncle’s wife continued to ask me to help her around the house and take care of the kids. It was hard there too.

I was 22. I went to school but I didn’t like it. They kept us inside and did not let us out. If we left, we would get punished. So I digged to make a hole out in the field and escaped. Before that, I called my friend Chú Dung whom I had met in the camp in Indonesia to come pick me up. He landed in Los Angeles but didn’t like it there so I told him to come down to San Jose. He came on his bicycle and we rode off to downtown. We watched movies and did all kinds of things. Then we rode back to the school so I could crawl back through the hole.

My retelling does not capture the full theatrical and funny persuasiveness in his words. There were moments where it was lighthearted and moments where it was serious, all in Vietnamese and broken English. He had become more open, more expressive, and more approachable since the time we drove to the airport in silence for my flight back to college — my mind racing on things to talk about.

Although this is just one account of his life, it is weaved into a much bigger story, the Vietnamese refugee journey — often told and controlled by white supremacists.

Raw, human stories drive action. There is power in collective narratives. This is why storytelling is so important. It allows the people who experienced and heard these stories growing up to take control of their own narrative, to define their own identity. People of color must tell their own stories and be at the heart of these narratives. They must write and tell their lived experiences in order to discredit the history used against them and shift the power structure.

I see fear, suffering, and loneliness among perseverance, resistance, hope, and resiliency. And knowing that I have someone like him close to me is a source of inspiration and pushes me to keep moving forward.

My dad’s story is not done. I haven’t heard everything yet and there will always be details that I may never know. But I will continue to listen and learn from his history, Vietnam’s history, America’s history. It will be a lifelong, learning journey, except this time, I choose to tell it.